Delivering government services through conversation design: Research summary

Canadians seek answers from governments on whatever device they have on hand - on their mobile phones, on tablets, computers and increasingly via voice. We wanted to learn more about how different kinds of interaction could help users find the answers they were looking for.

In one of our optimization projects, we set out to improve the success of Canadians contacting the Canada Revenue Agency. We experimented with different kinds of interaction designs.

We built a phone number look-up wizard as well as an experimental agent that worked as both a chatbot agent on a screen, and a voice agent, so we could compare the design processes and outcomes for each.

Definitions

Before we dive into our experiment, let’s go over a few definitions. As this field evolves quickly, definitions tend to change often.

Multi-turn interactions

Multi-turn interactions are those where some kind of back and forth sequence occurs to get to the right answer. They require logic in the sequence to help people only get the answer relevant to their situation.

Wizards are an example of multi-turn interaction.

Wizards

Wizards use a set of interactive questions to help people work through options to get the answer they need.

Wizards are becoming fairly common. They have been shown to increase task success in several of our optimization projects.

Conversational agents: chatbots and voice agents

For our purposes, we will define conversational agents as virtual agents that use conversation to arrive at answers for people.

The conversation can be:

- text-based (like in a chatbot on a web page)

- voice-based (like when using a smart speaker)

- some form of hybrid (like using Google Assistant on your phone)

Conversational agents take the interaction with users further than a wizard. They allow people to ask questions in their own words. Conversations follow the user’s flow, rather than forcing them into a specific sequence.

A well-designed voice interaction design seems like a usability dream:

- people don’t have to learn the design - they already know how to speak

- people can speak in their own words, rather than being forced to use the words you put on a web page

- voice interaction is accessible to people with visual impairments

How conversational agents work

For this project, we used a Google tool called DialogFlow™. The terminology we’re using comes from this tool. Terminology may vary using other tools, but the principles remain the same.

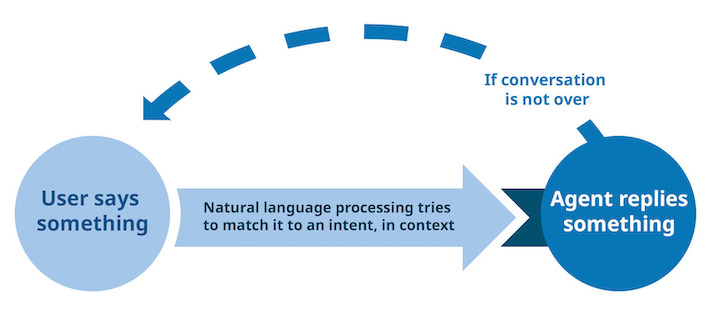

Conversational agents work like this:

- the user types or says something to express what they want to know - “What number should I call with a question about my tax account?”

- the agent matches what the user expressed to the set of “intents” pre-designed into the agent

- the set of possible responses is based on the context of the conversation - on what the user has already said, and the answers the agent has already provided

- the agent replies to the user with a pre-designed response for that situation - “Do you want to call about your personal tax account, or a business tax account?”

- the cycle starts again, if the conversation is not over

Chat cycle diagram

A visual example of how a conversation agent works. The user says something. Natural language processing tries to match it to an intent, in context. Then, the agent replies something. If the conversation is not over, the cycle repeats.

The “magic” in conversational agents is Natural Language Processing - a form of Artificial Intelligence. The agent uses Natural Language Processing to parse both the syntax and semantics of the conversation based on deep learning from a huge dataset of conversational language. So if a user says “I’d like”, the agent can understand that to match an intent that says “I would like ..” and an intent that says “I want”.

Building a conversational agent

At the moment, there is no magic to turning existing web content into a conversational agent. You have to design the agent, and every single intent, using conversation design. To do this, you need to research and plot out conversation flows.

The best way to start this process is to understand what you need to know to be able to provide a good answer. Starting with a wizard is great - you will already know what questions to ask to provide an answer for that topic. For example, for a Visit Canada wizard, you would need to know which country the person is coming from.

Write a few sample dialogues that might capture the same responses your wizard would give and then try them out with people. If you can, work with your call centre colleagues to get a sense of how conversations flow in the real world . When writing your sample dialogues, imagine the ideal back and forth that you would want between the agent and the user. This lets you see how the turn-taking and turn-skipping might happen.

Once you’ve written a few dialogues for the “happy paths” of your agent, you should also write sample dialogues for the “not-so-happy” paths. This allows you to see what could happen when the user doesn’t interact with the agent in the ideal way. Again, test these out with people. You can pretend you are the agent to get an idea of how the conversation might go. This style of testing is called ‘Wizard of Oz testing’ because you are speaking and thinking for the machine agent.

When you know how conversations could flow and how the conversational agent should interact with people, you can start to build the set of “intents” to guide the agent through the conversations. Next, test again…

The conversational experiment

At the beginning of January 2019, the Digital Transformation Office of the Treasury Board Secretariat started working on an optimization project with the Canada Revenue Agency. As part of the project, we were trying to help people find the right phone number to call for their particular question.

With the call centre and web teams, we crafted a set of realistic task scenarios. The scenarios were performed in usability test sessions, where we asked participants to find the answers for the scenarios on the website. Next we prototyped improvements to the site to solve the problems we saw in the baseline test. Then we tested the same task scenarios again with a new set of participants.

Prototypes

To test whether a conversational agent could help improve task success, we built 3 separate multi-turn interaction tools:

- a wizard where users selected from options right on the web page

- a chatbot where users opened it on the web page and interacted by typing

- a voice assistant where users interacted with their voice through a Google Home or Google Assistant on a phone

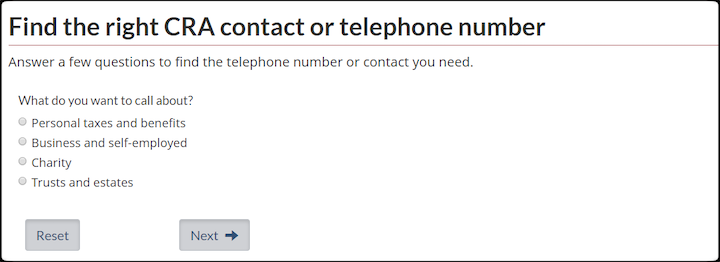

Wizard

The "Find the right CRA contact or telephone number" wizard displays questions about your call to help guide you to the answer you need.

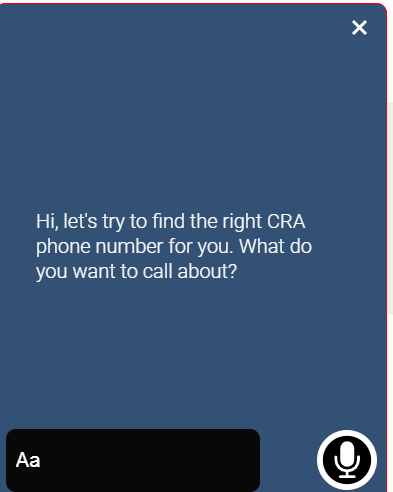

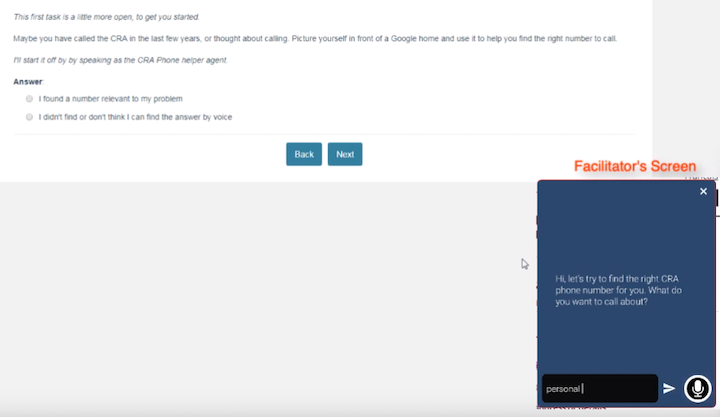

Chatbot

The CRA chatbot that appears at the bottom of your screen. It displays the text "Hi, let's try to find the right CRA phone number for you. What do you want want to call about?" People then type in their answer to get a response.

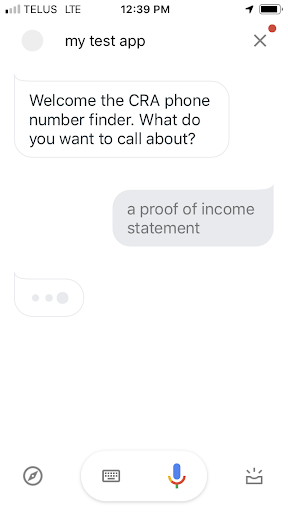

Google assistant voice agent

The CRA phone number finder Google voice assistant. It displays the text "Welcome to the CRA phone number finder. What do you want to call about?" The response is "a proof of income statement".

How we tested the design

We split the testing in 2 parts.

In Part 1, participants could use any section of the prototyped web pages to try to find the answers. They could use the wizard, the chatbot, or any other part of the website.

In Part 2, we made minor changes to some task scenarios, and asked participants to try to find the right answer using only the conversational agents. They tried to complete some tasks using only their voice (with the moderator speaking the part of the voice assistant based on the answers in the chatbot), and others using the chatbot on the prototype.

Conversational agent

To test the voice interaction, the participant spoke to the facilitator as if speaking to a Google Home device. The facilitator typed into the chatbot and spoke for the voice agent. The behaviour and wording of the chatbot was the same as it would be on a Google Home.

Results

To get an idea of how successful people were, we counted each time a participant tried one of the interaction tools to find an answer and noted whether they were successful or not.

Wizard: 33 successes out of 38 attempts (87% success rate)

Chatbot: 33 successes out of 41 attempts (80% success rate)

Voice agent: 21 successes out of 33 attempts (64% success rate)

We can’t conclude that these would be the same success rates in real life because of the relatively low number of trials. We do, however, get a good indication that it was easier for people to find answers using the wizard.

What we learned

Running this experiment helped us learn a lot about conversation design and how we can use it to improve services for Canadians.

Language model and training phrases

We learned a lot about training phrases and how to build the language model.

Welcome message: setting the context

The first interaction from the agent should welcome the user, and set the stage by telling the user what it can do.

In our experiment, we tried several different welcome messages:

- Hi, let’s try to find the right CRA phone number for you. What do you want to call about?

- I can help you find the right CRA number to call. What kind of problem do you need to call about?

- To make sure you get the right phone number for CRA, tell me what you need help with.

None of these worked very well.

Most participants simply ignored the message (both with the voice or chatbot). They started framing the conversation using their own words, based on their own assumptions of what the agent could do.

This led to some issues. For example, when the user asked “Can I get a number for…”, the agent matched it to the only “intent” that had the word “number” in the training phrases.

Looking for a number

Screen shows this text:

“Participant 4. Trying to find different numbers”.

Screen shows this text:

“Because he uses the word "number", the agent matches it to the "Business number registration" task”.

Participant:

“Can you please call the CRA business enquiry number?”

Agent:

“To get a business number, go to Business registration...”

Participant:

“Can you give me the number of the Canada child benefit number?”

Agent:

“To get a business number, go to Business registration...”

Participant:

“Can you give me the CRA business number that is related to mistakes and errors on payroll?”

Agent:

“To get a business number, go to...”

Screen shows this text:

“The training phrases were chosen assuming users would listen to the welcome message and understand that they didn't need to say "give me the number for...".

Training phrases and fallback options have to anticipate how users may not fully grasp what the agent can actually do.

In a conversation, everyone needs to be understood

People have many different ways of saying or writing the same thing. To handle the varied vocabulary users may throw at your agent, you need to carefully curate the training phrases for a specific intent.

For example, if the user wants to change their direct deposit information, they could say:

- direct deposit

- update my banking info

- change my bank account

- receive my payment in the right account

This is one of the main strengths of conversational agents: users don’t need to know how the organization would say something. They can use the words that make sense to them.

On the other hand, this makes it challenging for the designer. Even if Natural Language Processing helps, you still need to predict as much variance as possible for your training phrases.

For example, for the “Report a scam” task, we initially didn’t include the word “fraud” in the training phrases. When a tester used that term, the agent couldn’t match what the user was saying to the right “intent.”

Using a word that isn’t in the training phrases

Screen shows this text:

“Participant 15. Looking for the phone number to report a scam.”

Participant:

“Fraud prevention”

Agent:

“I’m having trouble understanding. What do you want to call the CRA about?”

Participant:

“Reporting a fraud”

Agent:

“I’m having trouble understanding. What do you want to call the CRA about?”

Screen shows this text:

“The agent is not able to match the word "fraud" to a response, because it wasn't in the training phrases.”

Screen shows this text:

“Participant tries "scam", which was in the training phrases.”

Participant

“Fraud or a scam”

Agent:

“To report a phone scam, call the Anti-Fraud line at 1-888-495-8501. Goodbye!”

Participant:

“Yeah! Eureka” (participant laughs…)

Screen shows this text:

“Building the right set of training phases is essential to match questions the proper answer”.

Vague questions are hard to answer

When people speak to a conversational agent, some are super specific, while others are very vague. The agent needs to be able to handle the whole spectrum.

Compare these:

- “I want to make a payment arrangement for my payroll taxes”

- “I need help with my account”

In the first case, the agent can match this to a specific intent: payment arrangements. It also has all it needs to give the proper answer because it knows the type of debt is payroll taxes.

In the second example, the agent cannot yet match the request with the payment arrangement “intent.” It must probe for more detail before knowing what to reply: “What do you want to do about your account?”

In this project, we also realized that words can have multiple meanings:

- my account - is the person talking about their bank account, or their CRA “My Account”?

- payment - is the person talking about a payment to the CRA, or a payment from the CRA?

- number - is it about a phone number, or an account number?

As a designer, you need to plan for vague requests, and design “intents” to handle them.

When the conversation goes wrong

People expect conversational agents to understand them as well as a human would. When the conversation doesn’t go as planned, users get frustrated if the agent isn’t able to fix it elegantly.

People don’t like to repeat themselves.

“Intents” have to be designed in a way that allows users to give as little or as much information as they want. When the user doesn’t give much, the agent needs to ask questions to fill in the gaps. When the user says a lot, the agent needs to retain these values in context and not ask for them again.

A participant who has to repeat something

Screen shows this text:

“Participant 7. Trying to find the phone number for the Canada Child Benefit.”

Participant:

“Next child… Next Canada child benefit payment due date.”

Agent:

“Ok, you want to call CRA about benefits. Which benefit do you want to call about?”

Participant:

“(Participant laughs) Child benefit”

Agent:

“Call the Benefits line at 1-8...”

Screen shows this text:

“Even though the participant had specified the type of benefit, they had to repeat it.”

“People expect conversational agents to understand and remember these details.”

When people say something not expected by the agent

In the course of the conversation, people may say something that is not what the agent needed to keep the conversation going forward.

Imagine that the agent asks the user to say A or B (for example, it is for a personal or a business account), and the user replies “yes”. When that happens, the agent needs to keep the conversation going forward by re-asking the question slightly differently, stating the options more clearly.

Example

User: I made a payment in the wrong account.

Agent: To find you the right number to call to transfer a misallocated payment, I need to know where the money is right now. Is it in your personal account, or in one of your business accounts?

User: Yes

Agent: Sorry, I didn’t get that. Where is the money right now: in your personal account, or one of your business accounts?

User: Oh, in my personal account.

Agent: To transfer a payment that was incorrectly made in your personal account, call the individual enquiries at 1-800-959-8281. Do you want to call now?

When the error handling works, users are happy. When it doesn’t work well, frustration happens.

Different expectations between chat and voice

Chatbots and voice agents are both conversational agents. The logic behind each type of conversation (spoken or typed) is similar. However, people behave differently and have different expectations when using each of them.

In our experiment, participants expected a richer experience from the chatbot. Instead of merely getting an answer, they wanted the chatbot to take advantage of the visual real estate and give more information. This could be, for example, links to where the answer is on the website.

“I would be more interested to get something like a top-notch answer (…) If I want to use a chatbot, I guess I would be more interested to see a layer, where you have also [sic] links that take you also [sic] to the website if you need to have more information…” - participant

On the other hand, people seemed to expect the voice agent to help them take the next step. They wanted it to do more than just give the phone number. They expected it to either offer to call the number for them, or send the info by email or text message.

Convincing users to use the chatbot

During Part I of our testing, participants were free to try to find an answer using any part of the prototyped website. Not a single participant clicked on the button to use the chatbot. Not one.

During Part II we asked them if they had seen the button at all, and if yes, why they had chosen not to use it.

Most participants said they didn’t use it because they didn’t think it would work well. When they tried it and saw that it did help them get an answer, most participants said they would use it again.

“Now that I have this positive experience, I probably would (use it) (…) I think sometimes it’s getting people used to having that experience – you don’t have that there now, so what are you going to do to convert people to use that chatbot?” - participant

The context in which people can access the chabot and the design used has an impact on this reluctance to use it. When designing a page that has a chatbot on it, test different designs with users.

In a follow-up experiment, we linked to the chatbot from the green “Find a phone number” button. This seemed to encourage people to use it, and it helped set the proper expectation, by clarifying exactly what the chatbot could do: find a phone number.

Wizard vs conversational agents: the task matters

Whether wizards or conversational agents work best depends on the specifics of the task. While the overall results favored the wizard, some tasks performed better with conversational agents.

Failing with the wizard, succeeding with voice

One of our tasks asked participants to find the number they should call if they needed to get an official proof of income. The task had some failures in the wizard, but it was almost 100% successful with the conversational agent. Several factors were at play:

- it’s easy to frame a question about official proof of income in your own words because it’s very specific

- the task was quite distinct from the other tasks that the agent could perform, making the intent matching easier

- there was only 1 answer to this question

- there wasn’t an intuitive way to group this with other contact tasks in the wizard

Using the agent to find proof of income

Screen shows this text:

“Participant 19. Fails to find the number to request a proof of income from the wizard.”

Participant clicks on a big green button labelled “Find a phone number”

The first question is “What do you want to call about?”

The options are:

- Personal taxes and benefits

- Business and self-employed

- Charity

- Trusts and estates.

The participant selects “Personal taxes and benefits”

The 2nd question is:

“What do you want to call about?”

The options are:

- Issues with signing in to My Account

- Change personal information, like your address, your name or your direct deposit/bank information

- Get a copy of your notice of assessment

- Get an official proof of income (option C printout)

- Information about your refund

- Information about benefits

- Make a payment arrangement

- Fix a misallocated payment

- Report a scam phone call

- Use the automated line to get other answers

- Other information

The participant scrolls down.

The participant clicks on “Contact the Canada Revenue Agency”, and gets back to the main Contact CRA page.

Screen shows this text:

“Participant doesn't seem to see the options in the list, and leaves the wizard by clicking on the link to the main contact page.”

Screen shows this text:

“Participant 8. Succeeds in finding the number to request a proof of income with voice.”

Agent:

“I can help you find the right CRA number to call. What kind of problem do you need to call about?”

Participant:

“Proof of income”

Agent:

“To get an official proof of income, sign in to My Account, or call our automated line, available 24/7...”

Screen shows this text:

“Using their voice, the participant simply has to say what they want to call about, and get the answer immediately.”

Succeeding with the wizard, failing with chat

On the other hand, some tasks performed better on the wizard. For example, all participants who tried to find the phone number to make a payment arrangement using the wizard succeeded. But more than half of those who tried to do it with the conversational agents failed.

Tasks that did not perform well with conversational agents had these characteristics:

- difficult to frame the issue in your own words

- easy to group with other issues in a wizard

- participants weren’t familiar with all the elements involved (like the fact that there are different phone numbers depending on the type of debt)

- the same issue requires a different answer, depending on certain variables

Using the agent to make a payment arrangement

Screen shows this text:

“Participant 8. Succeeds to find the number to make a payment arrangement for a corporate income tax debt using the wizard”.

Participant clicks on a big green button labelled “Find a phone number”

The text below the title is “Answer a few questions to find the telephone number or contact you need”.

The first question is “What do you want to call about?”

The options are:

- Personal taxes and benefits

- Business and self-employed

- Charity

- Trusts and estates

The participant selects “Business and self-employed”.

The 2nd question is:

“What do you want to call about?”

The options are:

- Issues with signing in to My Business Account

- Change information about your business

- Get a business number

- Make a payment arrangement

- Fix a misallocated payment

- Get help to file your T2 return online

- Report a scam call

- Other information about your business

The participant selects “Make a payment arrangement”.

The 3rd question is:

“For which type of debt do you want to take an arrangement?”

The options are:

- Corporate income tax

- Payroll debt

- GST/HST debt

Participant selects “Corporate income tax”.

Participant gets the answer.

Screen shows this text:

“The options offered at each step helped the participant get to the answer very quickly”.

Screen shows this text:

“Participant 6. Fails to find the number to make a payment arrangement for a payroll tax debt using the chabot”.

The screen shows a chatbot window, with these words:

“To make sure you get the right phone number for CRA, tell me what you need help with.”

Participant types:

“Payoff payroll deductions”

Chabot replies on screen:

“Sorry, I didn’t catch that. Can you tell me more about what you want to call about?”

Participant says:

“Ok… (laughs) hum…”

Participant types:

“Payroll deductions”

Chabot replies on screen:

“Ok, you want to call about your business. What is the reason of your call?”.

Participant says:

“Ok… call about your business… reason of your call.. Hum…”

Participant types:

“payoff payroll deductions”

Chabot replies on screen:

“I’m having trouble understanding. What do you want to call the CRA about?”

Participant says:

“Ok… it’s having trouble understanding what I’m trying to say...! ”

Screen shows this text:

“In the end, the participant wasn't able to frame the question in a way that the chatbot understands”.

There is a reason why a lot of tutorials on conversational agents use simple interactions like ordering a coffee or a pizza. People already have a learned mental model for these tasks. When you order a coffee, you already know that you will have to say the type, the size, how much sugar and milk, whether it’s “for here or to go”. It’s very easy to talk about this in your own words.

When there are a lot of variables involved, a user may have a hard time explaining what they’re looking for. They may not even know what information the agent needs to be able to give an answer. These types of conversations are difficult in person. They are even harder to have with a voice agent or a chatbot.

Conversational agents won’t fix bad content

There is this idea that robots will magically help content owners simplify their content. They won’t. If anything, complexity and poor content will be revealed and highlighted even more when trying to build a conversational agent.

To build an effective wizard or conversational agent, you need to have a perfect grasp of the questions people might have, of the answers they’re looking for, and of the information the agent requires to give the right answer.

There is no magic: conversation design is the key

Perhaps the biggest take-away from this experiment in conversational design is that there is very little “magic” involved. Simply put, if your Google Assistant or your Alexa replies to something witty or is especially useful in a specific circumstance, it’s because somebody, somewhere, planned for what you said, developed an “intent” for it using the right training phrases, and designed the right response for the agent.

Contrary to popular belief, you cannot ask a bot to scan your web pages, “learn” your content and develop conversations flows on its own. These agents also cannot get better over time “on their own”. A human needs to continually analyze data, find out where the conversations break down, and tweak the training phrases accordingly.

This is not to say that there will not be improvements to the automation of these agents in the future. The field is moving at lightning speed, and new tools are being developed very quickly. But at the moment, to develop a working conversational agent, you need to design them from the ground up.

That means time and people. This is not a ‘side of the desk’ project for your web team or your call center team. These tools are new service offerings and need to be resourced, designed, and managed as such.

Teams must follow sound conversational design principles, monitor how people interact with the agent, and make adjustments on a daily basis.

Working with a “launch-and-forget” mindset is never a good idea in the digital space. Doing so with conversational agents is even worse.

Finally, from a service perspective, having an agent that doesn’t help people is worse than having no agent at all.

Final word

Our experiment showed that wizards and conversational agents can be very powerful tools to help users complete their tasks. Instead of having users read through lines and lines of text and figure out what applies to them, this type of interactive design lets people give the necessary information to get only the answer that applies to them.

Conversational agents take it one step further by allowing users to frame their questions in their own words. They use their own mental model rather than being forced to recognize and understand the vocabulary we use.

But our experiment also showed that conversational agents involve a lot of design work and a lot of maintenance. At the moment, you can’t simply feed an Artificial Intelligence algorithm with content and let it build an agent - you need to design conversations.

We also learned that not all tasks are well suited for conversational agents in their current state. A lot of what we do in government involves personal identifiable information, or complex situations that require a lot of information to get the right answer.

If you have tasks that would benefit from a more interactive approach, building a wizard is likely the best first step you can take:

- wizards are easier to build and maintain than conversational agents

- wizards can simplify complex tasks

- the work done to understand the logic of tasks and the variables can be leveraged to build a conversational agent later

Before embarking on the conversation design journey, it’s important to choose the right task.

To justify the resources involved, it needs to be:

- one of your organization’s top tasks

- a task that people expect to complete quickly

- a task that already has a high mobile usage

- something that users can frame in their own words

- a task for which there is already a shared mental model or for which it would be easy for an agent to direct users through the conversation

- a task where you can trace clear boundaries between the possible answers

We know chat and voice are user interfaces of the future, and the future is now. As we keep moving forward and experimenting with these new approaches, we must keep in mind what’s most important: are we improving services for Canadians? Are we making it easier for them to complete their tasks?

Learn more

- Canada.ca optimization projects

- Optimize your content for voice search

- The magic of using interactive questions

- Google Conversation design learning material

- Alexa Design Guide

- DialogFlow documentation

- Voice First: The Future of Interaction? (Nielsen Norman Group)

Request the research

If you’d like to see the detailed research findings from this project, email us at cds.dto-btn.snc@servicecanada.gc.ca.

Let us know what you think

Tweet using the hashtag #CanadaDotCa.

Explore further

Read overviews of other projects with our partners

Page details

- Date modified: